Clifton Malone had a secret.

Clifton Malone had a secret.

A few people knew, sure. His wife, Ann, for one, and her parents, whom Cliff had lived with for a time. But no one spoke of it, especially not Cliff. Why would he? And what would he have even said? That an explosion in Korea had broken something in him, something that people couldn’t see? Or that he felt a stronger sense of duty to his family than to his nation?

Like so many men of his generation, Cliff’s story begins with an enlistment. An East Texas kid with a seventh-grade education, he followed a buddy into a U.S. Army recruiting office one day in 1950 and walked out a soldier. The Army welcomed him with vague promises about sending him to occupied Germany. Instead, by 1951 Cliff was in Korea in the thick of a new conflict, assigned to the 363rd Ordnance Ammunition Company.

Cliff would later describe for his family the long, cold nights he spent guarding a hillside munitions dump, fearing the Communists fighters who, it was said, would slip in under the cover of darkness and slit the throats of any American they found outside the wire. On these nights, Cliff admitted, he suffered from “nerves.” And it would only get worse.

In the fall of 1952 an explosion rocked the base where Cliff was stationed. A photo from that day shows smoke and shrapnel filling the sky above the barracks. Some of that shrapnel would end up in Cliff’s skull, sending him first to a field hospital, then back stateside to recuperate at Fort Hood.

Over the next couple of months Cliff requested and received two emergency leaves so that he could help care for his ailing mother, who was living in Lindale, Texas, near Tyler. On the advice of his mother’s doctor, Cliff applied for a hardship discharge, but that was denied. So, in January 1953, Cliff decided to simply remain in Lindale.

By this time Cliff’s nerves were severely frayed. In the parlance of the time he was “shell shocked.” He’d later admit that the thought of soldiering again made him “extremely nervous.” Nevertheless, he planned on finishing out his service, just as soon as he earned enough money pumping gas in East Texas to pay his mother’s hospital bills.

In the meantime, Cliff met and married Neva Ann Melvin, and the two of them made their home near Cliff’s mother. Despite being officially AWOL, a wartime deserter, Cliff never tried to conceal his identity, and even wore his Army uniform on occasion. With all the naivety of a 20-year-old, he must have figured the Army would be glad to have him back whenever the time was right.

Instead, a year later, Military Police apprehended Private First Class Clifton Malone. During his court-martial at Fort Hood, he laid out all his reasons for going AWOL, hoping for leniency. On June 17, 1954, Cliff was slapped with a dishonorable discharge and sentenced to a year of hard labor in the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Crowder, Missouri, of which he would serve six months before being paroled.

For the next forty-five years Cliff busied himself raising three sons and a daughter with Ann, working hard, serving as a deacon and Sunday school teacher in the Baptist Church, and teaching his children to love God and honor their country. Under the terms of his court martial, he was allowed to call himself a Korea veteran and display certain service ribbons, but he never once mentioned the court martial, his time in prison or his dishonorable discharge to anyone, including his children.

For much of that time, Cliff was also receiving treatment for anxiety. In a 2012 letter to the U.S. Army Review Boards Agency, his doctor, John Turner of Tyler, Texas, acknowledged that Cliff showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It’s unclear, however, to what extent Cliff attributed his anxiety to his time in Korea.

What is clear is that his dishonorable discharge ate at him. In 1999, after his grandson Patrick Malone enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, Cliff filed paperwork to have his case reviewed. He argued that if President Jimmy Carter could pardon Vietnam-era draft dodgers back in the seventies, why couldn’t a man who was just looking out for his family be afforded that courtesy?

In the same filing, Cliff cited his great-great-grandfather, who fought in the War of 1812, his great-grandfather, who fought in the Civil War, and his own father, who served in the peacetime Army in 1920, then again during World War II, as evidence of the Malone family’s patriotism, calling himself “the only black sheep” and expressing regret for his desertion.

In 2000, Cliff’s appeal was denied. With characteristic stoicism, he didn’t fight the decision. Instead, he vowed to take his secret shame to the grave.

Things became complicated, though, when Ann went into a nursing home in 2012. Cliff’s children applied for spousal medical benefits from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, but their claim was rejected. At first, Cliff was evasive as to why. Then one day he produced a stack of papers that told the whole story.

His children sorted through documents, trying to make sense of what amounted to Cliff’s confession. They also took it as a challenge, knowing full well that Cliff wanted his name cleared.

Like Cliff had done years earlier, his children petitioned the Army to reconsider the case. They argued that had the Army known what it knows now about PTSD back in 1952, Cliff never would have been ordered back to combat duty after he was injured. But that request was denied solely because Cliff hadn’t appealed the original rejection within the right timeframe. Again, Cliff accepted the verdict without complaint.

But when Cliff was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, his family renewed their efforts. Cliff wanted to be buried with military honors when he died, but that wouldn’t be possible with a dishonorable discharge hanging over his head. By this time another of Cliff’s grandsons, Chase Malone, was serving in the Army, and Cliff also wanted the boys to be able to attend his funeral in full military regalia.

Over the next few years, Cliff’s family wrote letters to Army officials and congressmen on Cliff’s behalf, but they were discouraged time and time again. Sadly, the matter was still unresolved when Cliff died in 2018. At his funeral, one grandson wore his military uniform, but the other didn’t. The family draped his casket in an American flag that had belonged to Cliff’s dad, but there was no honor guard and no gun salute. As far as the Army was concerned, it was as if a lifelong civilian had passed, not a man who had served and suffered for his country.

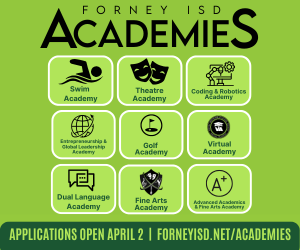

Finally, in 2021, another of Cliff’s grandsons, Matthew Malone, got in touch with Congressman Lance Gooden, who represents Texas’s 5th District in the U.S. House of Representatives. Matthew had filed another request to have the Army reconsider Cliff’s case, and he asked Gooden to at least help see it through the finish line.

Gooden agreed, and a couple of months later, the Malones received a letter from the Army Board for Correction of Military Records. “After careful review of your application,” it read, “full relief to your request was granted.”

Sixty-seven years after Cliff was convicted, he was officially exonerated on the grounds that he had indeed likely suffered from untreated PTSD at the time of his desertion, based on a guidance issued to all branches of the military in 2014 allowing for such amendments to veterans’ service records.

“Cliff Malone fought and bled for our country, and I’m happy that he finally received the recognition he deserved,” Congressman Gooden says.

Though they regret that Cliff wasn’t here to see the end result, which included his record being amended to reflect an honorable discharge, the Malone family now has some semblance of peace about the matter. They’re going to install a veteran’s memorial plaque at Cliff’s grave, and they’ll continue passing his story down through the generations, the story of a wounded hero who loved his country enough to sacrifice a piece of himself for it.